Writing Scripts

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 20 minQuestions

How can we automate a commonly used set of commands?

Objectives

Use the

nanotext editor to modify text files.Write a basic shell script.

Use the

bashcommand to execute a shell script.Use

chmodto make a script an executable program.

Writing files

We’ve been able to do a lot of work with files that already exist, but what if we want to write our own files. We’re not going to type in a FASTA file, but we’ll see as we go through other tutorials, there are a lot of reasons we’ll want to write a file, or edit an existing file.

To add text to files, we’re going to use a text editor called Nano. We’re going to create a file to take notes about what we’ve been doing with the data files in ~/dc_sample_data/untrimmed_fastq.

This is good practice when working in bioinformatics. We can create a file called a README.txt that describes the data files in the directory or documents how the files in that directory were generated. As the name suggests it’s a file that we or others should read to understand the information in that directory.

Let’s change our working directory to ~/dc_sample_data/untrimmed_fastq using cd,

then run nano to create a file called README.txt:

$ cd ~/dc_sample_data/untrimmed_fastq

$ nano README.txt

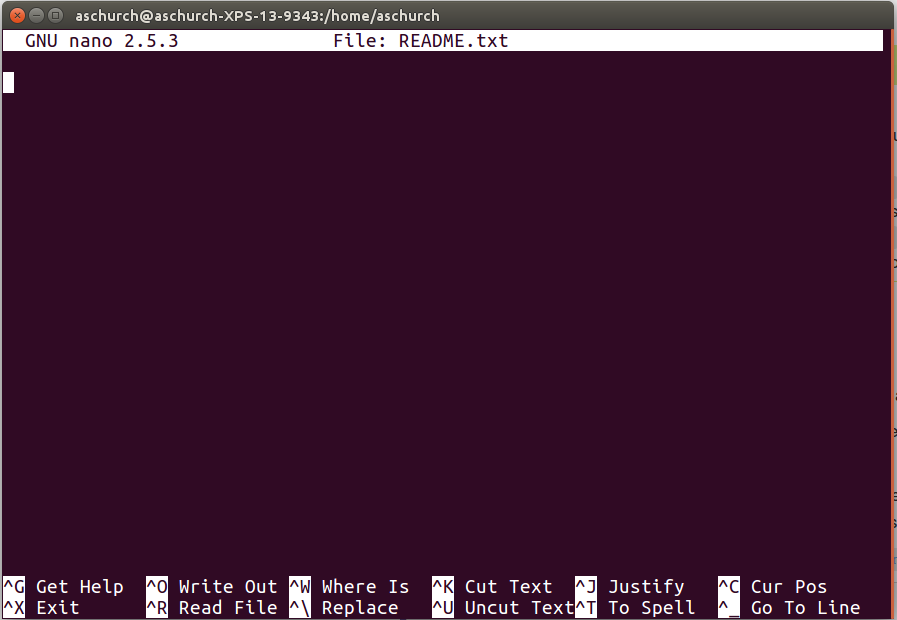

You should see something like this:

The text at the bottom of the screen shows the keyboard shortcuts for performing various tasks in nano. We will talk more about how to interpret this information soon.

Which Editor?

When we say, “

nanois a text editor,” we really do mean “text”: it can only work with plain character data, not tables, images, or any other human-friendly media. We use it in examples because it is one of the least complex text editors. However, because of this trait, it may not be powerful enough or flexible enough for the work you need to do after this workshop. On Unix systems (such as Linux and Mac OS X), many programmers use Emacs or Vim (both of which require more time to learn), or a graphical editor such as Gedit. On Windows, you may wish to use Notepad++. Windows also has a built-in editor callednotepadthat can be run from the command line in the same way asnanofor the purposes of this lesson.No matter what editor you use, you will need to know where it searches for and saves files. If you start it from the shell, it will (probably) use your current working directory as its default location. If you use your computer’s start menu, it may want to save files in your desktop or documents directory instead. You can change this by navigating to another directory the first time you “Save As…”

Let’s type in a few lines of text. Describe what the files in this

directory are or what you’ve been doing with them.

Once we’re happy with our text, we can press Ctrl-O (press the Ctrl or Control key and, while

holding it down, press the O key) to write our data to disk

(we’ll be asked what file we want to save this to:

press Return to accept the suggested default of README.txt).

Once our file is saved, we can use Ctrl-X to quit the editor and

return to the shell.

Control, Ctrl, or ^ Key

The Control key is also called the “Ctrl” key. There are various ways in which using the Control key may be described. For example, you may see an instruction to press the Control key and, while holding it down, press the X key, described as any of:

Control-XControl+XCtrl-XCtrl+X^XC-xIn

nano, along the bottom of the screen you’ll see^G Get Help ^O WriteOut. This means that you can useControl-Gto get help andControl-Oto save your file.

Now you’ve written a file. You can take a look at it with less or cat, or open it up again and edit it with nano.

Exercise

Open

README.txtand add the date to the top of the file and save the file.Solution

Use

nano README.txtto open the file.

Add today’s date and then useCtrl-Xto exit andyto save.

Writing scripts

A really powerful thing about the command line is that you can write scripts. Scripts let you save commands to run them and also lets you put multiple commands together. In the plot below, this is where you win, because you are automating your work.

One thing we will commonly want to do with sequencing results is pull out bad reads and write them to a file to see if we can figure out what’s going on with them. We’re going to look for reads with long sequences of N’s like we did before, but now we’re going to write a script, so we can run it each time we get new sequences, rather than type the code in by hand each time.

Bad reads have a lot of N’s, so we’re going to look for NNNNNNNNNN with grep. We want the whole FASTQ record, so we’re also going to get the one line above the sequence and the two lines below. We also want to look in all the files that end with .fastq, so we’re going to use the * wild card.

$ grep -B1 -A2 NNNNNNNNNN *.fastq > scripted_bad_reads.txt

We’re going to create a new file to put this command in. We’ll call it bad-reads-script.sh. The sh isn’t required, but using that extension tells us that it’s a shell script.

$ nano bad-reads-script.sh

Type your grep command into the file and save it as before.

Now comes the neat part. We can run this script. Type:

$ bash bad-reads-script.sh

It will look like nothing happened, but now if you look at scripted_bad_reads.txt, you can see that there are now reads in the file.

Exercise

How many bad reads are there in the two FASTQ files combined?

Bonus: How many bad reads are in each of the two FASTQ files? (Hint: You will need to use the

cutcommand with the-dflag.)Solution

$ wc -l scripted_bad_reads.txt537 scripted_bad_reads.txtThere are 537 / 4 bad reads in the two files combined. If you look closely, you will see that there is a

--delimiter inserted between the non-consecutive matches to grep. This accounts for the extra line. So there are 536 / 4 = 134 total bad reads.$ cut -d . -f1 scripted_bad_reads.txt | sort | uniq -c1 -- 536 SRR098026There are 536 / 4 bad reads for the

SRR098026.fastqfile and none for the other file.

Exercise

We want the script to tell us when it’s done.

- Open

bad-reads-script.shand add the lineecho "Script finished!"after thegrepcommand and save the file.- Run the updated script.

Making the script into a program

We had to type bash because we needed to tell the computer what program to use to run this script. Instead we can turn this script into its own program. We need to tell it that it’s a program by making it executable. We can do this by changing the file permissions. We

talked about permissions in an earlier episode.

First, let’s look at the current permissions.

$ ls -l bad-reads-script.sh

-rw-rw-r-- 1 dcuser dcuser 0 Oct 25 21:46 bad-reads-script.sh

We see that it says -rw-r--r--. This shows that the file can be read by any user and written to by the file owner (you). We want to change these permissions so that the file can be executed as a program. We use the command chmod like we did earlier when we removed write permissions. Here we are adding (+) executable permissions (+x).

$ chmod +x bad-reads-script.sh

Now let’s look at the permissions again.

$ ls -l bad-reads-script.sh

-rwxrwxr-x 1 dcuser dcuser 0 Oct 25 21:46 bad-reads-script.sh

Now we see that it says -rwxr-xr-x. The x’s that are there now tell us we can run it as a program. So, let’s try it! We’ll need to put ./ at the beginning so the computer knows to look here in this directory for the program.

$ ./bad-reads-script.sh

The script should run the same way as before, but now we’ve created our very own computer program!

You will learn more about writing scripts in a later lesson.

Key Points

Scripts are a collection of commands executed together.